Across the southwest, the bank of the Rio Grande is speckled with objects. There are things that people left behind before wading into the river — the final hurdle before reaching the U.S. — and other things they were forced to leave after being apprehended by Border Patrol agents, who instruct migrants to scrap anything “nonessential.” Mostly, there are clothes. But there are also hypothermia blankets, and baby bottles, and wallets, and prayer books, and toothbrushes, and headphones, and floaties small enough to fit a child.

In January 2024, photographer Alex Hodor-Lee set out to collect and photograph some of these objects after nearly a year of documenting migrants’ lives in New York and across popular border crossings in Texas. He scoured a popular crossing site in the small Texas town of Eagle Pass, saving anything that wasn’t too damaged — a spoon, a pair of red boxers, a green lighter. Abandoned belongings have always been somewhat common at border-crossing sites between the U.S. and Mexico, but it wasn’t until 2019, and the Trump administration’s Remain in Mexico policy, that volunteers began to notice migrants arriving at shelters with next to no belongings, often having lost critical identification documents. Others have speculated that agents are confiscating or forcing them to dump valuables. At one point, Hodor-Lee came across the very same shoe he was wearing, an orange Nike ACG. He brought the items back to New York in a giant duct-taped laundry bag as checked luggage.

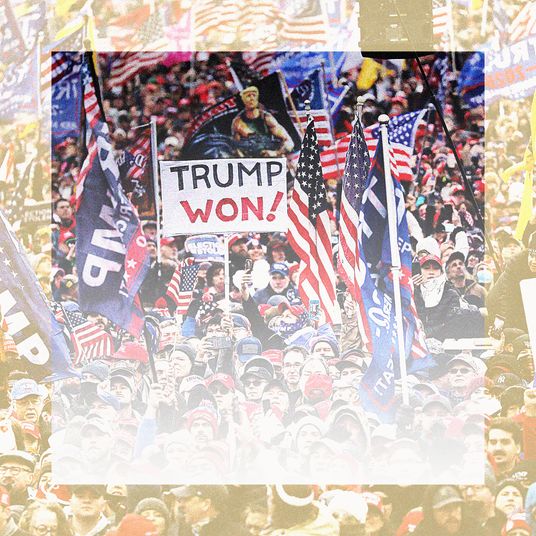

Hodor-Lee had spent the previous year learning how to photograph luxury fashion goods, and saw a commercial ubiquity in many of the items that migrants left behind. He was tired, he says, of seeing photos of migrants that emphasized their pain and strife, and, in turn, fueled a kind of political fantasy of what immigration looks like: a swarm of people wading through the Rio Grande; tearful good-byes between parents and their children after being detained by Border Patrol agents; rows of bodies piled into a caravan. Where photos of migrants that publications chose to circulate often forced a narrative, Hodor-Lee says the objects acted as “blanker canvases.”

On his first visit to the border, in March of last year, Hodor-Lee recalls asking a Venezuelan man that he’d met in El Paso if he could take his photo. The man agreed, but he hadn’t showered in a few days and was worried that if someone took a photo of him, wearing his unwashed clothes, it would perpetuate a stereotype. He was a lawyer in his home country, but people who saw the photo wouldn’t know that. For the first time, Hodor-Lee says, “it kind of occurred to me that, maybe, not taking these kinds of photos would be more helpful.” From that point on, he began first taking instant polaroids of subjects, so they could see what they looked like before taking their portraits. He let them keep them.