In late June, dozens of conservatives gathered on Capitol Hill for a forum on the failings of American capitalism. The event’s aesthetics were stereotypically Republican. There were the buttoned-up, apple-cheeked postgrads who’ve been staffing GOP Senate offices from time immemorial — the kind of young people whose bow ties tell you they have strong feelings about tax policy, birth rates, and Robert Bork. There were gray-haired Republican donors in dark blazers and prim dresses and a wide assortment of predominantly white middle-aged wonks, all mingling beneath the marble columns and chandeliers of the Russell Senate Office Building’s Kennedy Caucus Room.

While the forum’s crowd wouldn’t have looked out of place at a 1980s country club, its speakers’ words would have sounded alien to Republicans of that era. This was not an accident. American Compass, the think tank that had organized the gathering, aims to rip the GOP from Reaganism’s cold, dead hands.

“Capitalism is not working the way that it should,” declared the organization’s founder, Oren Cass, a policy nerd out of central casting, bespectacled and short with salt-and-pepper hair and a slightly nasal voice. “We don’t have the correct alignment between things that generate a lot of profit and things that are good for people,” he continued, explaining that only the government could bring the corporate sector and common good into harmony by channeling investment toward national priorities and income toward the working-class.

Although heterodox, Cass’s sentiments are not novel on the American right. In the years since Donald Trump’s election, skepticism about “free markets” has grown more common in red America. This is partly a product of Trump’s own irreverent attitude toward conservative doctrine in general and outright hostility to free trade in particular. But the former president’s affronts to Milton Friedman were typically more rhetorical than substantive, his appetite for self-promotion outstripping his interest in the nuances of public policy. Trump did not redraw Republican orthodoxy so much as he created space for others to attempt as much.

Various pundits and policy entrepreneurs have exploited that opening. In 2019, Tucker Carlson declared that rising crime and drug overdose rates in rural America were byproducts of the collapse in “male wages” wrought by offshoring, a trend that public policy needed to remedy. Market capitalism “was created by human beings for the benefit of human beings,” Carlson said. “We do not exist to serve markets.”

Meanwhile, “post-liberal” intellectuals like Patrick Deneen and Adrian Vermeule — who insisted that only a “liberal” would consider free markets more sacrosanct than “the common good” — gained a wider audience on the right. Other conservative thinkers followed their lead. In 2022, former editor of the Christian-right publication First Things Matthew Schmitz and former New York Post op-ed editor Sohrab Ahmari launched Compact magazine with an anti-woke Marxist. The official aim of their journal is to promote “a strong social-democratic state that defends community — local and national, familial and religious — against a libertine left and a libertarian right.”

What distinguishes Cass from the right’s other dissident intellectuals and polemicists is the realm in which he operates. The bulk of heterodox conservative economic thinking is produced in the airy climes of academia and “ideas” journalism. And it bears the imprint of these origins, evincing a keener interest in litigating philosophical first principles than in sweating the details of policy design. American Compass, by contrast, is a creature of Washington, D.C. It is not prosecuting the case against modernism in an ivory tower or mocking the “laptop class” in a digital publication. Rather, it is translating the populist right’s irritable mental gestures into model legislation for prioritizing workers in corporate bankruptcy and increasing wage subsidies for parents. And it is then pressing those proposals into the hands of Republican senators.

“My critique of the post-liberals is it remains very unclear to me what the actual alternative on offer is,” Cass told me. “Whereas, at Compass, we focus very intensively on having very concrete and actionable policy proposals.”

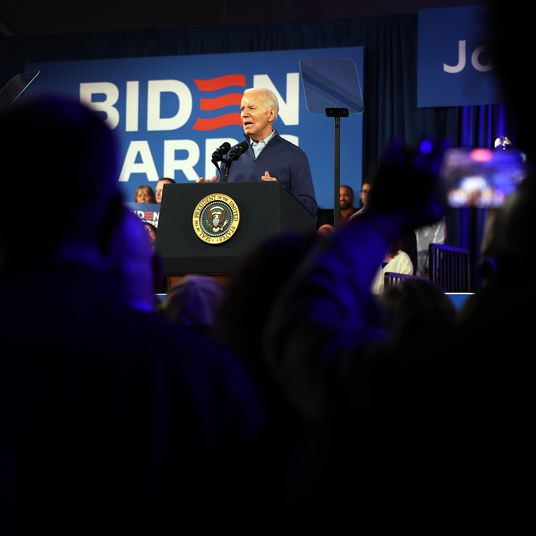

June’s gathering in the Kennedy Caucus Room was convened to celebrate the release of Rebuilding American Capitalism, a roughly 100-page handbook detailing the think tank’s vision for a new “conservative economics.” On hand were four of the GOP’s most ambitious young senators — Todd Young, Tom Cotton, Marco Rubio, and J.D. Vance — who touted their sympathies for Cass’s views on industrial policy, vocational training, trade, and organized labor respectively. “Under Oren’s leadership, and with the help of a small group of dedicated policy experts, American Compass has punched far above its weight,” Cotton said, commending Cass and his team for “pioneering new, bright policies that put American workers and families first.”

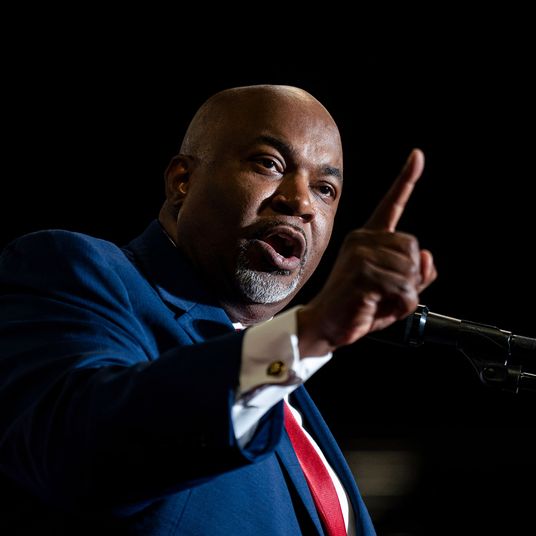

To Cass’s skeptics, his project is quixotic at best, and cynical at worst, since the concept of “pro-worker conservatism” is a contradiction in terms. The GOP, they say, is structurally committed to the interests of low-road capitalists. “The power base of the Republican Party remains the least imaginative, most hidebound element of the capitalist structure,” said Ahmari, who is supportive of Cass’s work but pessimistic about the near-term prospects of its pro-worker agenda. “It’s the regional tire distributor in the research triangle of North Carolina. And that guy is the most resistant to anything pro-labor.”

In the skeptics’ view, American Compass might succeed in providing bored conservative wonks with a venue in which to LARP as the brain trust of a Christian Democratic Party. It might lend the GOP a patina of intellectual vitality and populism. And it might give political writers fodder for “man bites dog” stories about how conservatives are turning against capitalism. But, in their view, the think tank will accomplish nothing for ordinary Americans. Congressional Republicans are still fighting to defund the IRS, cut the social safety net, and extend regressive tax cuts. The rest is noise.

Yet not everyone is so sure. The Hewlett Foundation and Omidyar Network, a pair of left-leaning philanthropies that aim to seed a “post-neoliberal” economic consensus, have collectively invested hundreds of thousands of dollars in American Compass.

“One of the lessons we take from past shifts in big-picture economic thinking is that paradigms change when they’re adopted as a ‘new common sense’ across the ideological spectrum,” said Brian Kettenring, director of the Hewlett Foundation’s Economy and Society Initiative. Felicia Wong of the progressive Roosevelt Institute also sees promise in Cass’s work, saying that “what Oren is doing could make a real difference in a Republican Party that wasn’t captured by a minority faction.”

Many iconoclastic conservatives, meanwhile, believe that they’re poised for breakthroughs. In Trump’s wake, the GOP has grown so ideologically unmoored that it declined to draft a platform in 2020. Something will need to fill that void. And Cass’s camp believes it has both the popular support and intellectual energy to do so. “The Republican Party is now without question the party of workers,” said Robert Lighthizer, Trump’s former trade representative and an American Compass board member. “The voters in the party are on the side of those of us who want a worker-focused — rather than corporate-focused, or efficiency-focused — trade policy.”

Recently, Trump called for imposing a 10 percent tariff on all foreign imports, which is one of American Compass’ signature policy proposals. And even the Heritage Foundation, long the GOP’s agenda-setter, has begun ceding ground to “common good” capitalism. American Compass doesn’t believe that it will remake the GOP in its image overnight. But in time, Cass thinks he can bend Republicans’ agenda into better alignment with their voters’ interests. “If all goes well,” he told the crowd of young Senate staffers in June, “this is where conservatism is headed.”

If Oren Cass has the politics of a right-populist insurgent, he has the CV of an old-guard Republican. Raised in central Massachusetts and educated at a progressive charter school, Cass wasn’t a self-conscious conservative in adolescence. But he bristled at the hypocritical pieties of his liberal classmates. “Everybody was extremely multicultural,” Cass said. “Unless you suggested that we should therefore tolerate Saudi Arabia’s treatment of women, at which point everyone was extremely not multicultural.”

To the extent that the young Cass betrayed conservative instincts, he skewed libertarian. From his post on the student council, he crusaded to end penalties for not completing one’s homework, arguing that the issue should be a matter of personal responsibility. At Williams College, these impulses coalesced into a worldview. The school’s introduction to microeconomics course awoke Cass to the miracle of free enterprise. The notion that the self-directed activities of autonomous people gave rise to a beneficent order — one that balanced supply against demand and encouraged nations to pursue their comparative advantages — resonated with his reverence for self-government. In a freshman-year paper, Cass declared, “There is no question that free international trade increases a society’s economic surplus.”

After college, he brought this outlook to the management consulting firm Bain & Company. Cass found the job intellectually stimulating. But over time, he grew dissatisfied. “It did frustrate me that the work we did was focused intensively on hitting short-run financial targets rather than actually building stronger businesses,” Cass said.

Cass’s attention turned increasingly to politics. In 2007, he took a six-month leave from Bain to intern on Mitt Romney’s presidential campaign. Four years later, Cass served as the domestic-policy director to Romney 2012.

Today, Romeny’s second campaign is remembered as the apotheosis of country-club conservatism. The former private-equity mogul centered his candidacy on the grievances of the successful, promising to give tax cuts to job creators and virtually nothing to the “47 percent” of Americans who believed that they were “entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you-name-it” — the so-called “taker” class. Yet Cass says it was Romney who opened his eyes to the bankruptcy of market fundamentalism.

Early in his tenure on the campaign, Cass was tasked with preparing a briefing on trade policy. He put together a PowerPoint rehearsing the eternal verities that he had learned in Econ 101, informing the Republican candidate that “opening new markets is crucial to economic growth and job creation.” Romney’s response was terse. “That’s fine,” he told Cass. “But what are we going to do about China?”

The question caught Cass off-guard. “It was not a question one asked in polite company back then, for fear of being revealed as an economic simpleton or, worse, a protectionist,” he later wrote in an essay on his ideological journey. Among the economic thinkers Cass had trusted in 2012, China was not a problem to be solved. Beijing’s communists may have used a combination of industrial subsidies, intellectual property theft, and labor suppression to flood the U.S. market with cheap goods, but if the CCP wanted to give Americans useful products in exchange for a bunch of IOUs, more power to them. Romney, by contrast, felt America’s lopsided trade relationship with China presented economic and national security challenges.

Answering the candidate’s query forced Cass to consult a wider range of economic thinkers. These included two of the Reagan administration’s lonely skeptics of free trade, Clyde Prestowitz and Robert Lighthizer. The two argued that conventional nostrums about the mutual benefits of open exchange did not apply to nonreciprocal trade relationships. The United States had routinely opened its market to nations that shielded their own country’s industries from competition through strategic industrial policies. Typically, these uneven trade relationships were initiated to serve geopolitical ends. “The United States might want Japan to stop manipulating its currency,” Prestowitz wrote in 2015. “But it also might want Japan to vote with it on something in the U.N. Washington has invariably yielded on the economic issue in order to prevail on the geopolitical issue.”

But market-fundamentalist dogmas denied the existence of any tradeoff between domestic and foreign policy goals, portraying the byproducts of realpolitik as economically optimal. In reality, Lighthizer and Prestowitz insisted, America’s tolerance of one-sided trade was corrosive to the productivity of domestic industry and the wages of U.S. workers. And this was especially true of its relationship with China, whose state capitalist system enabled extraordinary subversions of WTO rules.

Once persuaded that Econ 101 did not apply to China, Cass quickly came to question its relevance to contemporary capitalism writ large. He says that the quality of mainstream thinking on China made him “appreciate the extent to which a totally dogmatic orthodoxy that bore no relationship to reality could sustain itself for a very long time. I think it probably gave me a lot of skepticism about the quality of such orthodoxy.”

Rereading the classical economist David Ricardo, Cass found that the dominant theory of free trade’s virtues was premised on nationalistic assumptions: Ricardo had written that free trade was broadly beneficial for nations in part because “most men of property” were patriotic, and therefore preferred “a low rate of profits in their own country” to “more advantageous employment of their wealth in foreign nations.” As a result, countries could open up their markets without fear of investment migrating overseas.

It was clear to Cass that the patriotism of the rich could no longer be presumed. He has since written that capitalism advances the common good only when owners and workers are locked into mutual dependence. If firms cannot boost profits by combing the globe for cheap labor, they will need to do so by investing in productivity-enhancing technology. That technology will in turn make it possible for wages and profits to rise in tandem. But globalization broke the mutual dependence of America’s capitalists and laborers, allowing the former’s fortunes to swell while the latter’s wages stagnated. The inequities of this situation are, in Cass’s analysis, politically unsustainable. “A democratic republic’s vast working and middle classes will rightly reject such an arrangement,” he writes, “forcing elites to choose between restoring capitalism by constraining capital or entrenching their own economic prerogatives by subordinating the democratic process.”

Since 2012, skepticism of globalization in general — and America’s trade relationship with China in particular — has migrated from the GOP’s fringes to its center. This is partly a consequence of Trump’s election. The nationalist demagogue’s ascent accelerated a decades-long shift in the Republican Party’s class composition, with the GOP bleeding support among college-educated suburbanites and gaining it among white working-class voters in rural areas. As the Republicans’ mass base became increasingly weighted toward blue-collar laborers in deindustrialized regions, conservatives grew less enthused by free trade.

But the GOP’s hawkish turn on China also reflects the CCP’s growing authoritarianism, economic might, and geopolitical assertiveness under Xi Jinping’s leadership. Where the Pentagon once saw free trade as a geopolitical expedient, it now views the interdependence of the U.S. and Chinese economies as a national-security threat. In the Trump era, Robert Lighthizer went from being a gadfly to U.S. trade representative. Tariffs on Chinese imports and prohibitions on the sale of certain technologies to Chinese firms went from being disreputable ideas to bipartisan common-sense.

To an extent, Cass’s wager is that China can serve the same ideological function for his party that it did for himself. Which is to say, that the issue can tear a big enough hole in the GOP’s veil of orthodoxies to open up a broader vision of economic possibility.

In Cass’s account, America’s lopsided trade relationship with China exemplifies the free market’s inadequacies. Left to its own devices, the invisible hand will create jobs in Shenzhen instead of Youngstown. But it will also instruct America’s finest minds to innovate more addictive apps instead of more effective cancer treatments and channel investment toward high-speed trading instead of cutting-edge manufacturing. For Cass, the fundamental problem with market fundamentalism is that the private sector values profitability above all else, whereas true conservatives value strong families, strong communities, and a strong nation above maximizing Wall Street’s returns. And despite the fond imaginings of his party’s libertarians, conserving all that’s best in American life, and shielding markets from government influence, are antithetical endeavors.

Rebuilding American Capitalism has much to say about U.S.-China policy. It advises Republicans to prohibit American investment firms from holding Chinese assets, to bar Chinese-domiciled firms from accessing U.S. capital markets, and to impose high tariffs on Chinese imports. But the handbook also uses the right’s alarmism about the CCP to illustrate the broader principle that market incentives cannot be trusted to steer economic development, noting, “If satisfying the Chinese Communist Party offers the highest rate of profit, American business leaders have shown they will eagerly do just that.”

The think tank proceeds to articulate a comprehensive agenda for restructuring market rule in the realms of trade, industry, education, family formation, and labor relations. Taken together, this program would constitute a radical break from the status quo. In the country that American Compass aims to build, all foreign imports will be subject to a 10 percent tariff, which will automatically increase by 5 percent annually until the trade deficit is closed. All workers in a given industry will collectively bargain with all of their industry’s employers, establishing sector-wide standards for compensation and working conditions, and eliminating the risk that unionization will render an individual firm less competitive than its low-wage rivals. The National Labor Relations Board will have broader authority to crack down on union busting. Wall Street traders will have to pay a financial-transaction tax on the value of traded equities, bonds, and derivatives. A national development bank will ensure robust public funding for critical industries and infrastructure. In sectors deemed vital to the nation’s industrial base, 50 percent of all inputs will need to be sourced from the United States. Legal immigration will continue at its current level, but its composition will be shifted toward high-skilled workers, thereby insulating America’s most vulnerable laborers from foreign competition. And working families will receive a child allowance of at least $250 a month per child.

If this agenda scarcely resembles conventional Republican policy, it is also quite distinct from progressivism. Cass’s worldview is not social democratic so much as producerist — an ideology that venerates those who produce tangible wealth over those who live off financial chicanery or nanny-state largesse. American Compass retains the right’s conviction that simply giving money to the jobless poor perpetuates their indolence and withholds its child allowance from parents without earned incomes. Its program evinces little concern for environmentalism, counseling the abolition of the National Environmental Policy Act. The think tank’s preoccupation with increasing male wages specifically suggests a fondness for traditional gender roles. It is unabashedly nationalistic and hostile toward the undocumented. On China, its handbook is, at times, so belligerent as to lose contact with reality. A policy memo written by former Pentagon official Elbridge Colby asserts that “China supplanting the United States as the world’s most important economy would mean by definition a decline in Americans’ prosperity and economic security.” Yet the notion that Americans will automatically grow less prosperous if a nation of 1.4 billion people is allowed to have a larger economy than the United States is both maniacally jingoistic and patently false: If a nation necessarily grew poorer when another country’s economy “supplanted” its own, then the United Kingdom would be less affluent today than it was in 1916 when U.S. output first outstripped that of the British empire.

Nevertheless, Cass has attracted plenty of conservative criticism. The Capital Research Center, a right-wing “investigative think-tank,” has portrayed American Compass as a puppet of progressive philanthropists who aim to undermine conservatism from within. “With bedfellows that fit more comfortably at a Democratic Socialists of America meeting than the Knights of Columbus or Elks Lodge,” CRC’s Michael Watson writes, “for what does American Compass stand?”

As little as free-market conservatives care for Cass’s associations, they’re even less fond of his policy proposals. The Cato Institute argues that American Compass’ 10 percent tariff on all imports would choke off the flow of dollars to the foreign exchange market, thereby driving up the dollar’s value and putting U.S. exporters at a competitive disadvantage. This reality, combined with the retaliatory tariffs that such a policy would surely provoke, would arguably undermine American manufacturing, even as it drove up the cost of living for working-class consumers.

Angela Rachidi, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, argues that virtually all of Cass’s proposals are similarly self-defeating. “This idea that somehow policies that have freed up the market have caused all these problems is wrong,” Rachidi said. “I actually think it’s the reverse: There has been too much government intervention in the market, and it’s driven up costs for families.”

In the widespread conservative pushback against American Compass’ ideas, skeptics may see proof of its project’s hopelessness. But Cass and his sympathizers see the various jeremiads against them as signs that the old guard feels threatened. Rachidi herself says that she’s been surprised by how much traction “anti-market” arguments have gotten on the right in recent years, with Republican policymakers increasingly bringing up American Compass’ proposals in conversation.

The think tank’s influence may be most conspicuous among younger conservatives in D.C. “There’s definitely a generational divide,” said Patrick T. Brown of the conservative Ethics and Public Policy Center. “I think Oren speaks to the sort of younger Hill staffer type who is unsatisfied with where the country’s going.”

There is one thing that AEI and American Compass can agree on: The GOP lacks an affirmative economic vision. The party did not even bother drafting a platform in 2020, and its midterm campaign was almost entirely negative. Republicans ostensibly want to reduce the federal deficit. But as the debt ceiling standoff showed, Trump’s heretical opposition to entitlement cuts has rendered conservatives squeamish about cutting America’s largest social programs. The GOP’s leading 2024 contenders, for their part, have less to say about federal economic policy than about drag queens reading children’s books at public libraries.

To Cass, the party’s rudderlessness presents a historic opportunity. “Trump is like an earthquake. On the one hand, it’s a disaster and obviously causes a lot of problems. But it also exposes what was poorly built or outdated, and creates an opening to build something better.”

But others suspect that the GOP may choose to live among the ruins. A decade ago, Ramesh Ponnuru was waging a crusade similar to American Compass’ present one. Along with a coterie of other conservative intellectuals, Ponnuru called on the GOP to reorient its agenda toward the needs of its increasingly working-class constituency. The substance of this “reform conservatism” was much less radical than Cass’s. But it pushed in many of the same directions, calling for expanding the child tax credit and wage subsidies for low-income workers. Trump’s populist rhetoric in 2016 affirmed the “reformocon” analysis of where the GOP was heading politically. But his legislative agenda once in office — a failed bid to slash social benefits for working people, followed by a successful corporate tax cut — illustrated the movement’s impotence.

Ponnuru said that he thought he could “make the case that there was a better agenda than the old one that would deliver better results and would also serve the political interests of conservative politicians.” But a lot of Republicans “basically concluded they didn’t need a policy agenda in order to succeed. And the fact of the matter is that they have had decent election showings without running on much of a policy agenda at all.”

The GOP’s growing indifference to governing isn’t the sole obstacle in American Compass’ path. The bulk of the GOP’s big-dollar donors remain hostile to the think tank’s program. And although social conservatives have soured on “woke” capital, they haven’t all necessarily warmed up to Uncle Sam. “Most of the social-conservative world has given up on neoliberalism,” said Julius Krein, founder of American Affairs, a policy journal ideologically aligned with American Compass. “But at the same time, they’re still very wary of any sort of state power, since they think it will only be used against them. There’s an entrenched notion that conservatives can never do anything with the government. Anytime you have a government, it will be liberal, and therefore hostile to them in some way.”

Still, there are signs that American Compass is making progress. While Trump apes its trade policy proposals, Ron DeSantis has sought the think tank’s counsel. In addition to the four senators who attended Cass’s June forum, Josh Hawley is also squarely in the “common-good capitalism” camp. J.D. Vance’s senior policy adviser is a former American Compass staffer. And the think tank’s lobbying has yielded a wide array of heterodox legislative proposals. Vance alone has spearheaded bipartisan bills increasing safety standards for railways, empowering the government to claw back compensation from the CEOs of bailed-out banks, and requiring federally funded inventions to be manufactured in the United States. Tom Cotton has partnered with American Compass on a bill that would tax the endowments of wealthy private universities and use the revenue to provide blue-collar laborers with vocational training. Hawley has advanced Cass’s proposal to end normal trade relations with China and introduced legislation forcing down pharmaceutical prices. Todd Young has backed a bill restricting the use of noncompete clauses in labor contracts.

But few of these bills have attracted widespread GOP support. And as American Compass’ policy memos get translated into legislative text, they often get watered down. Cass has endorsed sector-wide collective bargaining agreements and giving workers representation on corporate boards. But American Compass’s partnership with Marco Rubio on labor policy yielded a bill that merely legalizes company-sponsored labor organizations (presently outlawed as a union-busting technique), and empowers such organizations to elect a nonvoting board observer. In other words, rather than requiring large corporations to give their workers full board representation, the bill gives such firms formal permission to let one of their workers watch their board meetings in silence. Cass hailed the bill as “innovative” and an “important step forward” for labor reform.

“I think the problem that American Compass faces structurally is that anytime any kind of conservative is willing to give even an inch on something related to the welfare state or labor, the Democrats immediately are like, ‘Great, let’s do it,’ and then that alienates Republicans,” said Matt Bruenig, founder of the People’s Policy Project, a left-wing think tank. “So to avoid that, they end up proposing stuff that actually just kind of sucks.”

American Compass’ progress in winning over the GOP’s top policy shops has been similarly equivocal. Over the past year, the Heritage Foundation has made a few fledgling gestures in Cass’s direction. Ahead of every presidential election, Heritage drafts a comprehensive policy guide for the next Republican administration. GOP presidents tend to ignore much of these blueprints. But in the Trump era, Heritage nonetheless exerted more influence on administrative staffing and policy than any other think tank. And this year, they let Cass co-author their guide’s labor platform, which endorses federal funding for vocational training and increasing the NLRB’s power to crack down on union-busting, among other things.

Heritage has also evinced sympathy for common-good capitalism as a philosophical project. Multiple conservatives I spoke with, including Cass, pointed to a paper that Heritage published in April as a watershed. In “Free Enterprise and the Common Good,” Heritage’s Alexander Salter pointedly declines to take a side in the fight between AEI and American Compass. This itself is remarkable, given Heritage’s history as a doctrinaire, pro-free-market organization. But Salter goes further, affirming Cass’s basic premise that the economy must be ordered to serve the general welfare and that households “dependent on the vicissitudes of commercial society” may lose faith in America’s political order.

And yet, Salter ultimately bends these high-level philosophical concessions into a case for catering to business owners. Salter agrees with Cass that workers dependent on precarious, low-paid employment will struggle to form stable families and communities. But he then suggests that trying to provide workers with more security through government policy would still leave them perilously dependent on forces larger than themselves. “The vagaries of politics are just as insecure a foundation for national renewal as the vagaries of markets,” Salter writes. In his account, the only stable foundation for social flourishing is personal wealth, as “the independence afforded by property ownership makes households less reliant on impersonal bureaucratic structures, whether of corporate firms or the administrative state.” Therefore, common-good conservatives must “focus on promoting small-business ownership.”

Of course, this is just a reiteration of American conservatism’s perennial valorization of the small-time capitalist. And as a proposal for delivering shared prosperity in a 21st-century economy, it is patently unserious. Every American can’t be a business owner. The vast majority of households in every industrialized economy have lived off wages. Policies that promote small-business ownership are not only irrelevant to the typical worker’s interests but arguably antithetical to them since small enterprises tend to pay worse wages than large firms, which can weather steeper labor bills through higher productivity. Nevertheless, Cass cited Salter’s paper as evidence that Heritage had turned a corner.

American Compass does not appear poised to transform Republican economics any time soon, but the various conservatives I spoke with tended to agree that it is making progress in a few policy areas. They suggest that the next Republican White House is liable to be even more anti-globalization and hostile to China than the first Trump administration. And if the next GOP president boasts control of Congress, there is a decent chance that they will enact American Compass-esque immigration proposals. “I think there’s much more of an interest in imposing requirements on employers who hire illegal workers,” said Henry Olsen, senior fellow with the EPPC. “Three or four years ago, there was complete resistance to mandatory use of E-Verify, and I think that’s fading fast.”

Some conservatives believe the GOP might set slightly less regressive priorities for tax policy. During negotiations over the Trump Tax Cuts in 2017, Marco Rubio and Mike Lee proposed cutting the corporate tax rate to 20.9 percent — instead of all the way down to 20 percent, as Trump had proposed — and using the resulting savings to increase the child tax credit for low-income households. “All of the promising and young people basically voted for the Rubio amendments,” Ponnuru said. “And it was much more of a group that you could legitimately describe as Old Guard Republicans who were on the other side of that. I think that’s a straw in the wind.”

Asked for a model of what a relatively pro-worker GOP fiscal policy might look like in 2025, some conservatives pointed to J.D. Vance’s proposal to scrap Biden’s electric-vehicle tax credit and use the consequent revenue to cut taxes on married EITC recipients.

Of course, the left-leaning philanthropies patronizing American Compass probably won’t be cheered by the thought that the think tank is successfully advancing immigration restriction, belligerence toward China, and anti-climate tax policies. A conservatism that mostly retains Reaganism’s fiscal priorities, while constricting global trade, severing economic ties between the world’s two great powers, and restricting admissions of low-skill refugees may be “post-neoliberal.” But it’s not obvious that this ideology would be more conducive to human flourishing than the one it displaced.

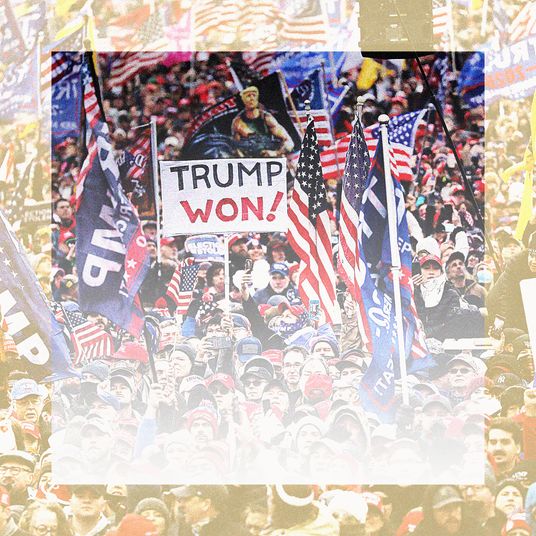

Further complicating matters, there is a disconcerting overlap between economic heterodoxy and January 6 apologism within the GOP. Two of the Republican senators most sympathetic to American Compass’ program — Vance and Hawley — are also among the party’s most vocal skeptics of the 2020 election’s legitimacy. Hawley voted against certifying that election’s results in Pennsylvania and Arizona, while Vance has claimed that the election was “stolen from Trump” and hailed the Capitol Hill rioters as political prisoners.

The fact that these senators evince sympathy for both Cass’s economics and Trump’s authoritarianism may not be wholly coincidental. In right-wing intellectual circles, antipathy for small government often comes paired with irreverence for liberal democracy. Vermeule and Deneen endorse both state intervention in the economy and heavy-handed regulations of cultural expression and sexual morality. As Vermuele writes, in a “common good” constitutional order, “Subjects will come to thank the ruler whose legal strictures, possibly experienced at first as coercive, encourage subjects to form more authentic desires for the individual and common goods, better habits, and beliefs that better track and promote communal well-being.” (Cass himself rejects the radicalism of his “post-liberal” admirers, arguing that America’s liberal democratic system “is worth preserving and rescuing.”)

For all these reasons, liberals may find it easier to applaud American Compass’ work in the context of divided government. With Washington split between Democrats and Republicans, Cass’s think tank has mostly served to facilitate bipartisan economic reform. When the Senate was debating the CHIPS Act, a bill promoting domestic semiconductor manufacturing, a Wall Street Journal op-ed lambasted the legislation. The bill’s Republican co-sponsor, Todd Young, credits American Compass’ rebuttal of the Journal with stiffening the spines of a critical mass of Senate Republicans, thereby enabling CHIPS to pass. Given how often Democrats need a small number of GOP votes to move legislation, the existence of even a few Republican senators who aren’t allergic to public investment can be consequential.

Nonetheless, common-good conservatives’ most ambitious economic proposals tend to boast more support from Democrats than Republicans. And this reality is not lost on all of the right’s heterodox thinkers.

“I have eyes to see that Democratic labor boards are better,” said Compact’s Ahmari. “Liz Warren has better ideas for taming Wall Street than anyone on the right … The political economy vision is all on the Democratic side. Whether you agree with every element of the CHIPS Act and Inflation Reduction Act, you just have to admit it’s a large vision of reshoring manufacturing.”

Ahmari sees mainstream Republican economic thinking as intellectually bankrupt by comparison. “Silicon Valley Bank fails, and it has to do with this long-term problem of regional banking in the United States,” Ahmari said. “What is the Republican account of what happened to Silicon Valley Bank? That it was too woke, the bank had gone woke. If you look up its board of directors, it’s almost all white guys. What the fuck are you talking about?”

Ahmari hopes that a series of electoral defeats will eventually force the GOP to reform its economic agenda. Until then, he expects his faction’s gains to be limited.

Congressional Republicans are doing their best to affirm that impression. In recent months, the House GOP’s largest caucus has called for gutting Medicaid and anti-poverty spending. The party leadership’s most ambitious economic policy proposal, meanwhile, is a regressive tax cut. As of this writing, there is chatter that House Republicans will force a government shutdown this fall unless Joe Biden agrees to cut food assistance to the poor. Trump’s policy team, meanwhile, is mulling another round of corporate tax cuts.

Cass concedes that Republicans aren’t as far along as Democrats on some issues. “But if we can win the argument on economic thinking,” Cass says, then there is far more hope of “building a consensus platform and ultimately a durable governing majority” within the GOP.

If Cass wins over the rising generations of Republicans, and intellectual bankruptcy starts costing the GOP elections, perhaps conservatism will head in a pro-worker direction. But for now, the American right’s compass points toward a more protectionist, authoritarian, and nativistic variant of Reaganism. Whether this constitutes progress will depend on one’s conception of the common good.