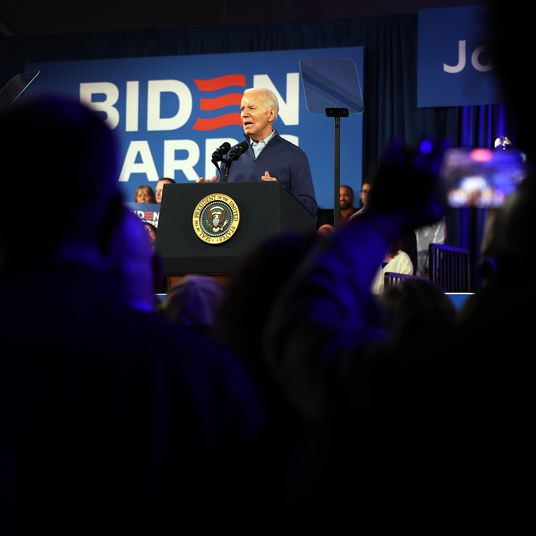

On Wednesday, President Joe Biden invoked the Defense Production Act to address the national baby-formula shortage, ensuring that formula manufacturers are first in line for any ingredients they require and directing the Pentagon to use its contracts with commercial airlines to speed the delivery of formula from overseas. It’s good, at least, to have a president who will wield the power of the executive branch to confront a national crisis. Donald Trump failed to invoke the Defense Production Act in the early days of COVID-19, dithering as the country was ravaged. The baby-formula shortage is a disaster for millions of families and Biden, well aware of his eroding popularity, is right to take it seriously.

But the disappearance of baby formula was decades in the making, a product of a flawed economic system that favors the bottom lines of a select few corporate giants. In good times, Americans don’t have to pay attention to this reality at all, as needed products make it to the shelves despite the risk that one day something might go terribly wrong. If all Biden does is return the system to its precrisis status quo, he will have been like all his recent predecessors — willfully blind to how monopolization creates critical weaknesses in the American economy.

The shortage began when a major producer of formula, Abbott Labs, shut down its main production facilities in Michigan a few months ago after they had become contaminated with the bacteria Cronobacter sakazakii, killing two babies and sickening two others. Abbott Labs is one of three major companies, along with Mead Johnson and Nestlé, that control the baby-formula market. As Matt Stoller notes, Abbott alone provides at least 40 percent of the baby formula in the United States, under the brand names Alimentum, Similac, and EleCare.

Abbott itself has not paid any financial penalty for the shortage because it’s an enormous conglomerate, a medical-devices and health-care company with a sideline selling nutrition — in April, shares actually rose in wake of the recall. Profits were up because Abbott is reaping a windfall from selling at-home COVID-testing kits. This week, the FDA struck a deal for Abbott to reopen its Michigan plant with new safety precautions in place. For Abbott, life hardly changes.

Since the baby-formula market is controlled by a select few incumbents, it is incredibly hard for new companies to compete. One attempt is by Bobbie, the first firm to come into the market in five years. The U.S., meanwhile, buys almost no infant formula from other countries; steep tariffs are imposed on most formula that is brought in. Regulatory barriers make it almost impossible for foreign formula-makers to sell to American customers.

The FDA imposes steep regulatory hurdles to producing formula, which, at first blush, may appear good — making it is not like designing a new brand of breakfast cereal. To get a product green-lit, a new manufacturer needs, at the minimum, protein-efficiency studies, nutritional tests to make sure it is suitable for infants, and approvals for new suppliers. Certifying a factory to make the formula is inordinately challenging and expensive.

The FDA goes much harder on potential new entrants than incumbents like Abbott, which was able to manufacture baby formula with shoddy equipment while falsifying records and tricking regulators. The FDA, though, did see the tainted baby formula months before the recall and chose not to act. Such deference — or lack of alarm — would never have been shown to a company without Abbott’s tremendous market share.

Finally, there’s the role of WIC. The federal government’s widely used nutrition program for women, infants, and children is by far the largest purchaser of formula in America, distributing more than half of all baby formula. Together, Abbott and Mead Johnson have almost all the WIC contracts with states. The government gets to pay a lower rate and, in return, the baby-formula giants access huge pools of consumers. If a mother, for example, gives birth and requests formula in a hospital, the formula will be manufactured by whichever company has the WIC contract for that state. A WIC contract guarantees favorable shelf space at retailers, building up brand loyalty over the long run and cementing the dominance of a particular baby-formula brand.

Reforming this system would be very challenging, considering the inherent value of WIC and the beneficial power the government has, in this instance, to negotiate lower prices. One trouble, though, is the rebate formula; having a sole-source contract distorts the nutrition market in individual states, where those competing against the conglomerate with the WIC contract may not bother putting alternatives on pharmacy shelves because so much of the market is already committed to purchasing from only one company.

At the minimum, the WIC-contracting process should be reformed so the auctions for contracts don’t create monopolies. It would be helpful to explore breaking off Abbott’s nutritional division from the rest of the conglomerate since manufacturing baby formula, clearly, is not a priority for the company, particularly if disastrous recalls don’t impact the share price at all. Getting more baby-formula manufacturers into the market — and allowing foreign imports — will be crucial to avoiding a shortage if one of the major U.S. producers screws up again. For now, the House legislation sending more money to the FDA to boost the formula supply is helpful, but isn’t going to attack the root cause of the problem. The FDA itself needs to be overhauled, and Biden can do this without congressional input. Beyond the failure of oversight with Abbott, why were critical supplies, like COVID tests, in such short supply for long stretches of the pandemic, and why did they cost more than European counterparts? For too long, the FDA has been permitted by both parties to be sclerotic.

Though off the table for now, more radical solutions should be considered too. Why not have the government manufacture baby formula? If moderates and conservatives will oppose full-bore nationalization of the industry, a public option for baby formula could be worthwhile, forcing Abbott and others to compete against the government while guaranteeing, in the event of another recall, baby formula for all. A government fail-safe could be readily available, always.