In the second chapter of The Kingdom and the Power, the 1969 book about the first 75 years that the New York Times was owned by the very same Ochs-Sulzberger family that owns it to this day, Gay Talese writes that “if the Times were covered as the Times covers the world,” then the office of its top editor “would lose much of the dignity and decorum that it now seems to possess.” Such was the goal of his now-famous book, and in a way it is also that of Adam Nagourney’s new book, simply called The Times, which picks up a few years after Talese’s book ends and continues until Donald Trump’s election. Its subhead reads: How the Newspaper of Record Survived Scandal, Scorn, and the Transformation of Journalism.

It’s the story of the paper trying to change with the times, while never forgetting that it is the Times — a “medieval modern kingdom,” as Talese called it back then, “a bible emerging each morning with a view of life that thousands of readers accepted as reality.” These days, it’s millions, reading it on their phones, or getting it in podcast form. But this is mostly a story about a lot of very smart and ambitious people caught in the thrall of their employer. And when you look too closely, as Nagourney does, there’s not always a lot of dignity or decorum to be found. The book’s pages are splattered with pulped ego, and the career body count is high.

“People who work there often judge their self-worth by how well they do there,” says Nagourney. “It’s part of the DNA of the Times and it’s part of the reason the newsroom is so tightly wound.” It was late one night in mid-September and we were meeting at JG Melon on the Upper East Side. We got one of those good round tables in the corner up front by the bar. “People who leave the New York Times frequently find that they feel like they’ve fallen off the face of the earth,” he adds between bites of a cheeseburger.

Nagourney, who is 68, was first hired at the paper in 1996 (to cover Bob Dole’s campaign) and is still employed there, writing about politics. He took a leave to work on this book and says that the Times had no approval over what he put in or left out, and did not review it prepublication. He began working on it in 2016, after convincing the publisher of the paper at that time, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., to sit for interviews. Nagourney also interviewed every living former executive editor; that would be Max Frankel (he ran the paper from 1986–1994), Joe Lelyveld (1994–2001, and again for a spell in 2003), Howell Raines (2001–2003), Bill Keller (2003–2011), Jill Abramson (2011–2014), and Dean Baquet (2014–2022). “What I didn’t realize was that once Arthur agreed to do it, everyone was going to agree to do it,” says Nagourney. “Lelyveld, Keller, Raines, and Abramson shared documents with me. Lelyveld and Keller literally handed me boxes of stuff and said, ‘Have at it.’”

Who could resist one last chance to … correct the record? When I called around last week to old-school Timesfolk to ask if they’d read an early copy yet, people kept asking me, with a mixture of panic and pride, Am I in there? I was really involved with … and then they’d recount some long-ago controversy. (Jayson Blair! Judy Miller! Raines versus Abramson! Abramson versus Baquet!)

Nagourney ends the book just before Arthur Sulzberger Jr. — who’d taken over in 1992 from his father, Arthur Sr. — passes the paper to his son, A.G. Sulzberger, on January 1, 2018. A.G. was just 37 when he took over and has since overseen a vast transformation. What was once a daily newspaper of record is now a global continuous news source, endlessly churning out journalism at all hours and in all formats. There are 10 million subscribers and lots of moving parts, not all of which are particularly newspapery — games and recipes and product reviews and wellness content. It is an efficient, if more staid, bureaucracy these days.

“One of the things I thought about when I first started writing the book,” says Nagourney, “was how the era of these quirky, big characters is just mostly gone.” He begins with Abe Rosenthal’s appointment as executive editor in 1977. The editors back then behaved like Greek gods, acting on whims, driven by gigantic egos and petty feuds, indifferent to the harm done to the mortals below. Rosenthal was like Zeus, hurling thunderbolts, confident of his aim (there was no Slack back talk or employee tweetstorms on Mount Olympus). “You could really punish people then,” says Nagourney. He documents how vengeful editors would banish reporters or rivals who crossed them, sticking them with far-flung assignments or dead-end beats. (This absolutely still happens there, though to a lesser degree.) Each various executive editor had his or her court of loyalists, but there’s treachery on every other page, and the book reads like an internal affairs report at points.

I wonder how much has really changed, and what it is about the Times that drives people mad — or is it that one must be mad in order to ascend there? “There’s an old line,” says Nagourney of those on the editor track, “that no one’s career at the Times ever ends well. I don’t know if that’s true or not. It’s always been an up-and-out kind of place. You keep moving up, and if you don’t succeed, you’re out … That’s part of the culture of the place. It doesn’t strike me as tough and mean a culture now as it was 20 years ago.”

The book details a kind of mania among a class of editors clawing upward even as the power and prestige of the paper is being undercut by the internet and the collapsing economics of the business. It used to be that editors at the highest echelons could jump, when it was clear there wasn’t enough room at the top for them, to the Chicago Tribune or the Philadelphia Inquirer or the Los Angeles Times, where they could keep doing great journalism in provincial exile. But the internet, after first nearly wiping out the Times, made it even bigger and more powerful, gathering the readers and resources of these other lesser papers into its own orbit, blotting out almost everyone else. Which only made the mania more acute.

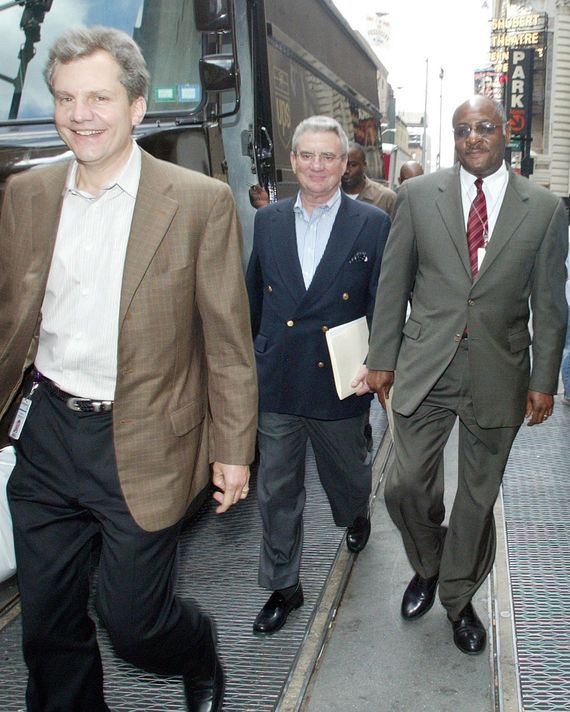

One scene in the book recounts how, in 1997, Lelyveld told editor Gerald Boyd he was being passed over for a managing-editor job in favor of Bill Keller. Boyd would later write that “the name felt like a dagger thrust into my gut. My emotions swirled together: hurt, betrayal, embarrassment, abandonment. But bitterness — bitterness reigned.” He would eventually get the job in 2001, after Raines took over. But then Sulzberger fired Boyd and Raines in 2003 as a result of the Blair scandal, among other errors of judgment. Boyd became something of a recluse and died of lung cancer in 2006. One of the most scalding chapters of the book is about his funeral, which became a setting for more Times-ian recrimination among his old colleagues. Had they done wrong by him?

Keller’s editorship was jinxed by Judy Miller and the paper’s role in the run-up to Iraq, and those sections of the book are among the roughest on Arthur Sulzberger. Nagourney prints a letter Sulzberger received in 2005 from his rival, Washington Post publisher Donald Graham, after an article appeared in The New Yorker, written by Ken Auletta, which quoted Arianna Huffington trashing Sulzberger, and Talese remarking that “You get a bad king every once in a while.” “So you’re criticized by Arianna — God! — and Gay Talese, who hasn’t been at the Times in 40 years,” Graham wrote to Sulzberger, “and a lot of anonymous cowards. This is just a tempest in a teapot.”

In writing about the Abramson years, Nagourney shows her struggling against the breakdown of the church-and-state-like separation between the news and business sides of the company, and how then-CEO Mark Thompson (who is now running CNN) was her bête noire. Nagourney writes that “Thompson assured Abramson he had no desire to tell the newsroom how to operate. She never believed him. And in truth, he arrived in New York with the grandest of ambitions.” He writes that, by the time she is fired by Sulzberger, “Abramson was battling the publisher, the publisher’s son, the newspaper’s chief executive, her managing editor, and much of the masthead.”

He describes how, in 2009, Abramson wooed “the publisher’s son” into the Times fold when he was 28 and working as a reporter at The Oregonian. At first, he demurred, worried he was not yet worthy of the Times. At one point, he had to be given the legacy talk by his grandfather, Arthur Ochs “Punch” Sulzberger, who “pulled him aside at a family gathering to remind him of the importance of the Sulzbergers to the Times, and of the Times to the Sulzbergers.” Shortly after he arrived, he was told his full name — Arthur Gregg Sulzberger — contained too many characters to fit on a print byline. Thus he became A.G.

Nagourney writes how A.G. “was different from his father in many ways. He did not eat meat and was so thin that he was almost spectral in his bearing. With his dark, deep-set eyes and full head of hair (he would begin buzzing his head to a close crop when he began balding in his thirties) he looked more like his grandfather than his father. He had an ease that recalled Punch Sulzberger, and a confidence and self-assurance that his father had lacked at his age.” Which reads a little obsequiously. How can readers trust Nagourney to write honestly about the place while he’s still on the payroll? “That’s a fair question,” he says. “I think the answer is that it’s almost all about the past.” Is there even anything in here that is going to piss off the current publisher? “I don’t know, actually,” says Nagourney. “Maybe something about his father.”

He says that, compared to his father and grandfather, A.G. Sulzberger was a much better reporter, “and that shows in how much he pays attention to the report every day.” If the publisher is more involved in the news report than ever before, it follows that the executive editor wields less power than in the past. “I think Jill would agree with that,” says Nagourney. “In fact, what was going on with Jill was that she felt she had less and less authority over the news reporting.” The current executive editor, Joe Kahn, who joined the Times in 1998, appears in the book only fleetingly. He was the foreign editor in 2014 when Abramson flew to China so the two could try to convince Chinese authorities to stop blocking the Times website there. It was on the flight back to America that Abramson read for the first time the “Innovation Report” — an internal study authored by a not-yet-anointed A.G. Sulzberger that spelled out the company’s way forward in the digital era, and, Abramson felt, her doom. “She read the report as a commentary on her performance. And it was written by the publisher’s son,” writes Nagourney. “I am fucked, she thought.”

There is an elegiac quality to this book. It’s easy to forget now that the Times is so massive, but up until recently it was a newspaper that catered to under 2 million subscribers, who cherished it for its singularity: the stacked headlines, the lofty writing, the serious-minded Manhattan snobbishness it exuded. Many reporters who work there now are dismayed that New York Times seems to be vanishing as it morphs into a far more mass-market enterprise, with many more readers than before, half-following the live updates on their phones and chewing over the vastly expanded “Opinion” pages while Wordling daily. It’s all about the bundle.

The highest expression of newswriting at the Times has always been what’s called a “lede-all.” As Nagourney writes, a lede-all is “an authoritative article that captured a moment in history … they required a combination of command, meticulous organization, precision, speed, writerly flair and a sense of history and Times style.” You know your career is going well there when the editors start turning to you for these stories. A young Howell Raines was called upon to write the lede-all the day Ronald Reagan was shot. (“A Secret Service agent writhed in pain on the rain-slick sidewalk …”) Nagourney wrote the lede-all the night Obama won. “I remember Bill Keller coming over and giving me a hug at the end of the night,” he says, smiling to himself, “and working with Jill Abramson to figure out the exact lede.”

They’ll never do away with them completely, but at the new Times, the lede-alls are increasingly out of fashion. The emphasis now is on the “Live Desk,” which puts out those short-burst news briefings that are thrown together into incoherent, rolling bulletins during particularly newsy moments. The cascading information keeps readers glued to the app, refreshing for more, but many reporters regard it as unrewarding work. Die-hard Times readers can recall trenchant ledes they’ve loved or stories that touched their hearts. No one is ever going to say, Remember that great live briefing … When I profiled Kahn last year, he and Baquet told me they see this as the future of the newsroom. They think that, on breaking news, the “Live Desk” can raise their game to the level of CNN, with its monstrous news-gathering operation. (Which means they are now going up against their old comrade, Thompson.) The Times is so big it hardly regards the other newspapers as the competition at this point.

But has it sacrificed too much of its own newspapering spirit? The Pulitzer-winning sports department was killed last week; sports is now outsourced to the Athletic. The “Metro” section has lost most of its grit and granularity as the paper plays to an audience far beyond its old core readership on the Upper West Side and the commuter suburbs. The editorial board, which once spoke with what they called “the voice of God,” turned into reality television. Headlines read like Axios now. (There’s a lot of “Here’s What You Need to Know.”) Product reviews such as “The 5 Best Vibrators of 2023” are rather unbecoming of the Gray Lady. The datelines have been done away with because they cause “confusion” to the new “digital readers.” All of which might be a fine and proven way to get more — more clicks, more “engagement,” more subscribers, more whatever — but it also means that it just all reads a lot like everything else out there now.

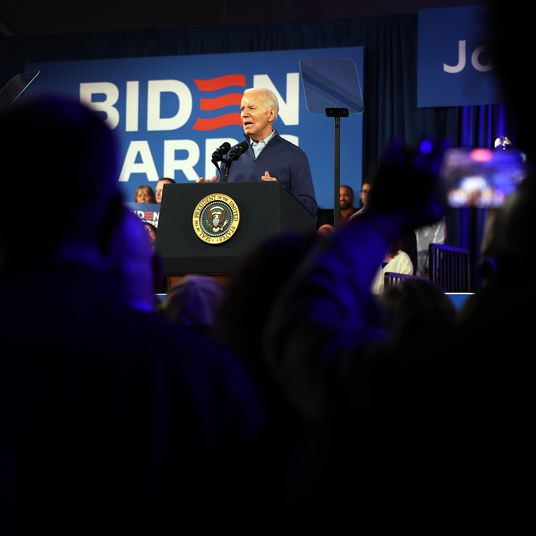

As I try to get this old-school reporter to tell me what he really thinks of all this new devilry, a man at the next table over approaches our corner of the pub. “Sorry, I can’t help but overhear everything you’re saying,” he says. “I’m just a reader, and it’s like the intelligence level of that paper dropped massively. You’d open the paper and it’s not like it was some crazy Hemingway stuff, but it was good writing by a smart person to a smart person that treats the issue with nuance. Now it almost feels like, if you read the British government website, they’re trying very carefully to say things as cleanly and simply as possible. Here’s what you need to know about this. This person is good. This person is bad.” Nagourney sips his coffee and considers this. “Were your parents New York Times readers?” he asks. Yes, says the man. “I grew up reading that paper and watching the NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. It’s very sad for me, like, there is no Jim Lehrer, and there is no New York Times.” He won’t tell us his name, only that he is in his late 20s, from Manhattan, and that, while he was appropriately horrified by Trump’s election, he eventually found the Times coverage unreadable because “the paper kept on writing in this very agitated manner for years.”

The reporter eyes him a bit skeptically. Even though he is about to publish a big, long book about the newspapers’s myriad screwups and all the self-destructive, power-mad people who populated the place, Nagourney does not seem to like hearing his Gray Lady dissed by this outsider. Nagourney is a Times loyalist, a lifer, and so what if the paper is now playing with sex toys and slinging clickbait? If that is what it takes to pay for reporters to be on the ground in Ukraine, and for sprawling front-page longreads about the Darién Gap or a deathly drought afflicting the Tigris and the Euphrates, so be it. After the man walks away, Nagourney turns to me and asks quietly, “Would the New York Times have survived the way it was?” For a while there, not everyone was convinced it would.

In true Times fashion, there is already lots of huffy whispering about Nagourney’s book. Many Times people tell me they think it was journalistic malpractice that the book’s timeline ends in 2016, since the toxic tango between Trump and the Times is the single most interesting thing about the paper’s recent history and journalism writ large. And because the Trump years were so important in the company’s economic turnaround. As recently as 2016, there were only 1.8 million digital subscribers.

A telling moment appears at the end of Nagourney’s book. It describes a meeting between top Times editors and executives that took place on the 16th floor of the building one week after the 2016 election. The Times had apologized for missing the election, and furious liberals were threatening to cancel their subscriptions en masse because they felt the paper was somehow responsible for Hillary Clinton’s loss. Then–chief revenue officer Meredith Kopit-Levien (she has since become CEO) informs the room that, in fact, the liberals were not going to abandon them — just the opposite: “‘Let me start with the good news,’” Nagourney reports her saying. “‘What we have seen is the number of cancellations have dropped off significantly. Unbelievable performance.’” The paper added 41,000 new digital subscribers that week — the largest weekly subscription increase since the introduction of the paywall.

While the book is stuffed with Old Testament gossip, don’t expect to find out more about the recent controversies or changes at the paper. There’s an epilogue, but it’s thin. Nagourney doesn’t really delve into the firing of his good friend James Bennet, or the criticisms of “The 1619 Project” by historians, or the Pulitzers awarded for coverage of the Trump-Russia conspiracy that wasn’t. He says he didn’t want to report on the people with whom he still works. He basically skips over Baquet’s entire tenure as editor.

“I think there’s a great book to do post-2016,” says Nagourney, “but I think it’s way too soon to do it. I think that you’d want to examine the way Trump changed the paper. We don’t really know where it’s going to end up. We’d want to examine, in my opinion, the relationship between Joe Kahn and A.G. Sulzberger. We’d want to examine the continued struggle of the paper to figure out how to appeal to subscribers without walking away from being the Times — in other words, just going after traffic. I think that’s all stuff being worked out now.”