All Elizabeth Henson wanted last January was to find a hot porn video to share with her husband, who was off in a different city prepping to sell their old house. As the wife of an active-duty coastguardsman, she’s often in a long-distance relationship, and porn helps bring them together. “We use it for date night,” she said, explaining that the two of them log in to Pornhub while video-chatting each other, pleasuring themselves to the same XXX scene. “It’s no different than both of us logging in to Netflix to watch a movie. It’s just more intimate.”

But this time she wasn’t greeted with Pornhub’s typical selection of hard-core previews. Instead, Henson was taken to a brand-new landing page for Louisiana residents such as herself. In order to proceed any further, she was told, she’d have to verify that she was at least 18 years old by entering her Louisiana ID into a third-party platform called Allpasstrust. The blockade was the result of the state’s HB 142, a new law mandating age-verification systems for websites that offer users access to “material harmful to minors.”

Pornhub’s landing page assured Henson that the verification process would be quick and easy. It wasn’t. In fact, she couldn’t use Allpasstrust at all. Although she lives in Louisiana, she remains a Texas resident thanks to a federal law that allows servicemembers and their spouses to maintain legal residency in other states for certain purposes like voting. “It’s not my choice to be in Louisiana,” she said, noting that changing her residency every time her husband was reassigned would come with a whole slew of financial and tax implications — ones that aren’t worth taking on just to prove to Pornhub that she’s 40.

Henson was stopped only temporarily, though. After conferring with military friends, she learned there was an easy workaround: a virtual private network that enabled her to fool Pornhub into thinking she wasn’t in Louisiana so she could carry on with her date night as planned. “It’s not like most kids don’t know how to use a VPN, so what’s the point?” she asked.

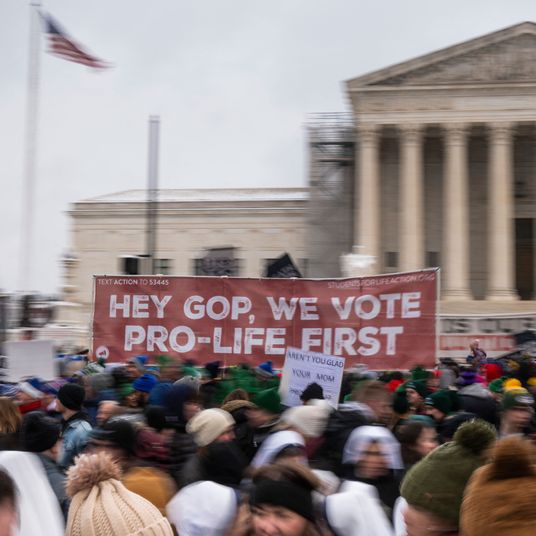

The point, according to proponents of the Louisiana law — and its copycats in Utah, Montana, Mississippi, Virginia, Arkansas, and Texas — is protecting children, full stop. At a time when young people are in the midst of a major mental-health crisis, one that some have attributed to the internet, barricading porn access is presented as an obvious first response to the emergency. It may not be foolproof, but if it prevents porn from warping children’s minds, it’s worth it. For many, it’s no more complicated than that.

With their focus on cutting-edge identity-verification technology, these laws may seem like a wholly new legal innovation, but they’re just the latest battle in the long war on porn, one that has pitted First Amendment freedoms against the desire to shield children from any potential harm — and revealed, again and again, that “porn” is often in the eye of the beholder.

The spark that ignited the latest attack on porn came from Howard Stern.

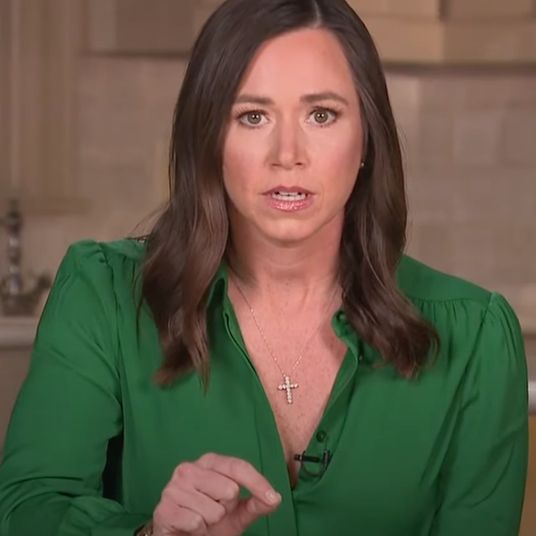

In a December 2021 interview with him, the singer Billie Eilish confessed that she’d begun watching porn at 11, which she blamed for her failed relationships as an adult. When newly elected Louisiana lawmaker Laurie Schlegel read about the interview, it sounded all too familiar from her career working with people addicted to porn as a licensed professional counselor. Still, hearing someone as prominent as Eilish speak so vulnerably about her own sexual and romantic struggles moved her. “It sent me on a journey to see what other countries are doing,” said Schlegel, who wrote HB 142.

Over the past two centuries, government hostility to obscenity has ebbed and flowed, peaking during periods of repression, like the era of the Comstock laws or the Reagan years, and recently becoming more laissez-faire. But with the advent of the internet, it seemed as though porn had finally won the upper hand and was practically ungovernable. In the U.S. early attempts at regulating online porn, like the 1998 Child Online Protection Act (COPA), were deemed unconstitutional by courts that found them to be overly broad in their restriction of free speech. Other countries have had slightly more success. In 2017, the United Kingdom mandated age verification for porn sites, though two years later the proposal fell apart over regulatory and technological obstacles. In 2020, Germany moved forward with its own age-verification law, subsequently ordering the country’s largest internet service providers to block a major porn site. Canada, Australia, and France have all either considered or passed age-verification laws, and the U.K. is making another attempt.

None of those countries have American free-speech protections, however. The First Amendment stopped COPA in its tracks, and a German-style age-verification bill would probably be dead on arrival in the U.S. But Schlegel’s brainchild isn’t a criminal law enforced by the government. Her bill is enforced through civil lawsuits that, crucially, can be filed by an individual who suffers “damages resulting from a minor’s accessing” online porn, not unlike the broader “bounty hunting” enforcement strategy of the six-week abortion ban in Texas.

Ever since HB 142 was enacted, both the porn industry and a variety of creators whose work might potentially be considered “harmful to minors” have been panicking. “The chilling effect here is the point,” said Michael Stabile, the communications director for the Free Speech Coalition, an adult-industry trade group. Stabile is convinced that the real goal of such age-verification laws is nothing short of shuttering the adult industry. Porn, he told me, is “an easy bogeyman to go after,” with few people in power willing to advocate for such a stigmatized art form.

Schlegel, however, believes these laws are a no-brainer. The chances of a child encountering porn are “100 percent,” she said, adding that “the average age is between 10 and 12” when children are first exposed to porn. Statistics on youth porn consumption can be hard to pin down, but clearly young people are watching porn. Early this year, Common Sense Media — a nonprofit group known for rating content aimed at kids — released a research report compiled from a survey of 1,358 young people between the ages of 13 and 17. The study found that 73 percent had watched pornography online and that 54 percent had first seen porn before the age of 13.

How that exposure affects young people is harder to determine. Researchers can’t analyze the effects of porn viewing on young minds as it’s both illegal and unethical to show minors porn, even in the name of research. Or as Common Sense put it, there “has been little research on the effects of pornography on adolescents, and so we should remain alert to alarmist headlines about pornography being a public health crisis or destroying America’s youth.” The research that does exist on porn and adolescents is hardly conclusive: Consumption can increase sexual aggression, anxiety, and depression, but it can also improve body acceptance and knowledge of sex and anatomy — particularly for LGBTQ youth, for whom porn is often the only source of queer-inclusive representations of sexuality.

In the absence of clear answers, there are deep divides about how to protect children — and, perhaps more thornily, what “protecting” them would even mean. The adult industry’s preferred approach is a combination of content filters that allow parents to block their child’s access to porn and comprehensive sex education in schools. But in state capitols, on both sides of the aisle, the answer is straightforward: age verification. It’s offered up as a common-sense fix: If you have to show an ID to buy beer, why not porn?

The bills appear unstoppable in their popularity. Tellingly, even legislators with reservations seem leery about opposing them. When Schlegel’s colleague Senator W. Jay Luneau weighed in on HB 142, he said he was told “unequivocally” by a constitutional lawyer “that your bill is clearly unconstitutional. When I was sworn in as a senator, I raised my right hand to God and took an oath to uphold the Constitution. And when we pass legislation that we feel reasonably sure is unconstitutional, we’re probably violating that oath.” Yet he still couldn’t resist the bill’s promise that it was protecting children. “I think this is important enough to support it and hope for the best,” Luneau concluded before voting in favor.

A VPN might have saved Elizabeth Henson’s date nights, but she didn’t just want a technical workaround. She wanted to get rid of the law and was connected to a little-known but powerful lobbying group already gearing up to sue Louisiana.

Founded in the early 1990s, the Free Speech Coalition was originally envisioned as a legal-defense fund for adult companies targeted by prosecutors. In the decades since, it has repeatedly beaten back the anti-porn forces. In 1997, it shut down a proposed California tax on pornography. In 2002, the Supreme Court found in its favor in Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition, deciding that a definition of “child pornography” written into law by Senator Orrin Hatch — one which did not require media to contain children or even sex in order to be criminalized — was overly broad. In 2016, the organization’s efforts sank California’s Proposition 60, a ballot initiative mandating condoms in porn productions filmed in the state.

Today, FSC is led by Alison Boden, a onetime CEO of the fetish site Kink.com. Twenty years ago, Boden entered the adult industry as a wide-eyed sex educator eager to bring a feminist sex shop to her Pittsburgh community. “My personal background comes from a place of activism, and it ended up in business,” she said. Under Boden’s tenure, FSC began lobbying Congress to outlaw what she says is financial discrimination by banks against the adult industry, such as when Wells Fargo terminated sex-worker bank accounts en masse. But then HB 142 passed, and Boden’s days have been filled by pushback against age-verification laws in the form of court challenges against Louisiana, Utah, and Texas, where FSC last month obtained a preliminary injunction against the law taking effect. “The restriction is constitutionally problematic because it deters adults’ access to legal sexually explicit material, far beyond the interest of protecting minors,” the federal judge said in his ruling, which Texas is expected to appeal.

A diverse group of complainants are fighting back. In addition to Henson, there’s D.S. Dawson, a Utah-based erotica writer who uses Pornhub to advertise his stories; John Doe, an attorney who represents members of the sex industry and considers being asked to upload an ID to visit his clients’ websites a gross violation of his privacy (a core value that’s also behind his decision to be an anonymous plaintiff); and O.School, a sex-education site that fears its willingness to talk about sexual pleasure might lead some states to label it porn. The plaintiffs are united by a basic argument: That by limiting adult access to constitutionally protected and fully legal speech — which, yes, pornography made by consenting adults counts as — age-verification laws are an unconstitutional violation of their First Amendment rights. And, as was the case when the Supreme Court found COPA unconstitutional, there are other, far less burdensome ways to prevent young people from accessing porn online that don’t violate the rights of adults who wish to consume and distribute legal adult content, such as parental filters.

Another argument they make is that age verification poses a danger to privacy. “The Oregon DMV just had a massive security breach,” said Henson. “And somehow I’m supposed to trust that that’s not going to happen to a third-party app?” One adult webmaster, who asked to remain anonymous so as not to draw potentially litigious attention to their site, told me that their largely queer and trans user base expressed concern that age-verification information might be used to identify and persecute them in states such as Texas, which has an age-verification law and is cracking down on LGBTQ rights.

Another has to do with the cost, which can range from 25 cents per ID check (a rate one webmaster said they were given by the age-verification platform Yoti) to 65 cents (what FSC says Allpasstrust charges). In other words, a website getting 1 million visitors per month would spend at least $250,000 verifying their ages. “The fact that age verification is so expensive to the point where most businesses can’t afford to do it as prescribed in the laws means that this is an unconstitutional prior restraint on speech,” Boden said.

Schlegel has no sympathy. “The porn industry is a multibillion-dollar, very highly unregulated industry, and that’s why you’re seeing them getting sued for having child pornography [and] people’s rape videos — they’re wholly unregulated,” she said. “And they’re only responsible when someone makes them responsible.”

The porn industry is very highly regulated, through both federal laws and less formal regulation conducted by banks and credit-card processors, but what Schlegel said also masks a deeper issue raised by age-verification laws. To most people, the targets of these laws are obviously the massive multinational porn conglomerates for whom age-verification fees are minor, such as the parent company of Pornhub. But the laws would affect all small, independent sites whose minimal or nonexistent profits can’t cover the cost of age-verification services.

The laws seemingly exempt massive, multibillion-dollar social-media sites where young people can and do encounter porn, such as X (formerly Twitter). The text of HB 142 notes that age-verification law only applies to sites featuring a “substantial portion” of objectionable content, defined as more than 33.3 percent of a website’s total material. How that is calculated is never made clear, but what is clear is that the provision is a massive exception for social media. Is the porn video a teen finds on an NSFW sub-Reddit less harmful because Reddit is also full of less obscene content? Or are lawmakers simply eager to give a carve-out to massive tech companies whose legal budgets could easily tie up age-verification laws in court?

Schlegel explained her legislation was simply an attempt to create a category that would include as many adult sites as possible to balance adult freedoms with the government’s interest in protecting children. “With this goal in mind, I consulted with lawyers and decided to take a measured approach. I wanted our bill to be narrow in scope and not be overboard,” she said.

Smaller operations don’t always feel protected by that measured stance. Take, for instance, Oh Joy Sex Toy, a sex-education webcomic run by Portland-based couple Erika Moen and Matthew Nolan. At first glance, Oh Joy Sex Toy seems exempt from HB 142’s purview. The site is clearly educational in nature. Although Moen and Nolan occasionally run explicitly erotic comics, they say those make up less than a third of their library — putting Oh Joy Sex toy in compliance with the vague standard set by HB 142. Multiple lawyers have told them they have no cause for concern, according to the couple. And yet Nolan can’t shake the anxiety that they might get swept up in an anti-porn crackdown. “I feel very disarmed by it all. It does mean I have to live in perpetual fear,” he said. A sex-ed comic book jointly authored by the couple has come under fire from a number of parents across the country who consider the book far too hot for library shelves. There’s nothing stopping those same parents from suing Moen and Nolan under HB 142.

“The larger project is to close off the internet,” said Stabile. “It’s not a coincidence that this is happening at a time when they are simultaneously declaring all sorts of LGBTQ content, all sorts of content on sex education or race, as pornography or obscene.” Porn may be the enemy lawmakers are eager to target, but their weapon of choice stands to cause a lot of collateral damage.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly described who can sue under HB 142.